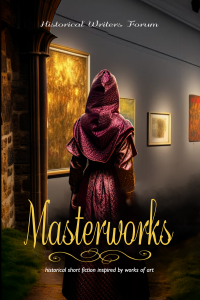

I was thrilled to be asked to host a blog post for E.M. Swift-Hook as part of a blog tour for the anthology, Masterworks, in which she wrote a wonderful short story called Blood on the Mountain, set in Prague. During her research, she came across a curious mode of assassination that seems to be unique to that city.

Here is Eleanor to tell you all about it.

Such an arresting word ‘defenestration’.

The kind of word that sticks in the mind.

Unfortunately, its definition is not very delightful at all. It is the act of throwing someone out of a window but carries the implicit intent of killing them by doing so. Unlike many words in the English language, we know when it was invented and why.

It was invented in 1620 to describe a specific event that happened in Prague in 1618.

But in Prague, defenestration has something of a history.

The 1618 event that led to the creation of a new English word was not the first time the action it described had happened there. Indeed, the practice of throwing people from windows already had precedents in Prague and therefore carried a great deal of symbolism. To understand what was really going on in 1618, we need to look briefly at those.

On the 30th July 1419, the Hussites, a popular religious movement which sought urgent reform of the Catholic church, marched on the New Town Hall in Prague to demand the release of their co-religionists. A stone thrown from the town hall window hit their leader. Infuriated, the Hussite protesters stormed the town hall and threw the leader of the council and several councillors from a high window, killing them.

By Øyvind Holmstad – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.

On the 24 September 1483, fearing that a new king might deny them those hard won religious rights, the Hussites seized control of Prague and hurled the leading councillors from the windows of the Old and New Town Halls. Some of the unfortunate men were killed by the fall, some were already dead when they were thrown out. The religious rights of the Hussites were confirmed soon after and Bohemia continued under its Hussite majority.

It is against this backdrop that we have to view the events of 23 May 1618.

Less than a decade before, the previous King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf (who incidentally lived in Prague rather than the usual Habsburg capital of Vienna), had signed a letter which guaranteed freedom of worship for the Protestants in his kingdom of Bohemia and essentially established a Protestant state church there.

When Rudolf died, his successor, both as King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, Matthias, confirmed the Letter of Majesty, which enshrined those religious rights. But Matthias was not a young man and had no children. So he wanted to be sure his heir was well established. On being assured their religious rights would be upheld, the Protestant Bohemian Estates agreed to elect his chosen heir, Ferdinand, as their new king.

That was the interesting thing about Bohemia. Unlike most nations where the crown passed down the generations automatically, it had an elective monarchy. Admittedly once elected, the job was for life, and it was a given that the elected king was always going to be the next Habsburg emperor, but even so, the Bohemian Estates did get that vote.

The problem was Ferdinand wasn’t just a Catholic. He was a fanatical Catholic and a champion of the Counter-Reformation. Before his election, Ferdinand gave assurances he would uphold the Letter of Majesty. But his interpretation of it was not the same as that of the Bohemians or of Emperor Mattias. Mattias had allowed the building of new Protestant churches on royal lands. Ferdinand claimed the Protestants had no right to do so. Even worse, he also declared that the Protestant estates could no longer meet.

The Protestant nobles weren’t going to stand for that.

Led by Count von Thurn and supported by a great crowd of ordinary people, they cornered the four Catholic lords that Ferdinand had appointed to see that his will was enacted.

When it became clear that two of those lords didn’t care what was going on and weren’t going to try and speak up for the majority of their countrymen, Thurn declared “You are enemies of us and of our religion”. The duo was thrown out of the window of one of the castle towers, together with their secretary.

However, there is a bit of an unexpected twist in this tale.

That window the three men were thrown from was some seventy feet (21.3m) above the ground. But all three survived. Two were able to get up and run off, the third was unconscious and carried away swiftly by his servants. We don’t know for sure why they survived, clearly something broke their fall. Protestant propaganda said it was a heap of manure set by the wall of the tower. The Catholics claimed it was divine intervention, but whatever it was the two noblemen lived to take refuge in the fortified palace of one of Ferdinand’s loyal supporters in the city. The secretary raced with the news to Vienna and was later ennobled by Ferdinand as Baron von Hohenfall, or Baron of Highfall.

The Protestant estates went on to elect a new king, the leading Protestant prince of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick, Elector Palatine. He was married to Elizabeth, the daughter of James VI and I, King of Scotland, England and Ireland.

By the time the new royal couple were crowned in November 1619, Matthias had died, and Ferdinand was emperor. Now he had all the power that allowed him to command armies to redeem what he saw as his stolen kingdom.

Thus, the stage was set both for the outbreak of war and for my story ‘Blood on White Mountain…

E.M. Swift-Hook says: In the words that Robert Heinlein put so evocatively into the mouth of Lazarus Long: ‘Writing is not necessarily something to be ashamed of, but do it in private and wash your hands afterwards.’ Having tried a number of different careers, before settling in the North-East of England with family, three dogs, cats and a small flock of rescued chickens, I now spend a lot of time in private and have very clean hands.

https://eleanorswifthook.com – Website

https://amazon.co.uk/gp/product/BOCKM276KE – Masterworks UK

https://amazon.com/gp/product/BOCKM276KE – Masterworks US